Last week I led a seminar for a group of high school English teachers on how to teach racially sensitive (or racially charged) literature. Many were teaching The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which uses the n-word 231 times. In their school district, the book is “restricted,” meaning they cannot teach it without going through mandatory sensitivity training because parents have challenged it so often.

I can’t tell you the number of teachers who came up to me during breaks and after the seminar who were worried about being a white teacher teaching racially charged material. They were nervous about raising the issues of race or dealing with students of color’s emotional responses.

When conversations about race relations come into the English classroom, it can be challenging because it isn’t a history class. We want to look at the story themes, rhetorical devices, and other literary conventions. It’s tempting for some students (and the teacher) to distance themselves from the structural racism in the text — the realities of unearned privilege and unearned disadvantage — through the comforting neutrality of simplistic clichés like “slavery was bad.”

The reality is you have got to have a plan. Here is a five point action plan to help you create the right conditions for presenting and teaching challenged books in a culturally responsible way. (The post is a bit long but worth it).

Cultivate your “distress free authority” to teach the text.

In order to successfully facilitate the discussion of racially sensitive literature, it is important for you to have what John Heron, author of The Complete Facilitator’s Handbook, calls “distress free authority.” Distress free authority means that you recognize not only your right, but your responsibility to confidently help your students navigate the text.

- Do your own inside work around issues related to the racial legacy of American society, especially systemic unearned privilege and unearned disadvantage. This means you are clear on your own personal socio-political positioning and what it means for you to teach a racially sensitive novel from this racial, ethnic, or gender perspective.

- Know your emotional triggers around these topics. If a student’s response triggers you, practice the idea of “zen in ten.” Give yourself ten seconds before allowing your brain to respond or react. Practice deep breathing. Prepare yourself and have a strategy in case it happens, like simply returning to the discussion norms.

- Come to the teaching and facilitation of the novel each day with a sense of inner calm. You are responsible for creating and maintain the right social and emotional climate in the room. Come to class rested and unstressed on the day of heavy class discussions.

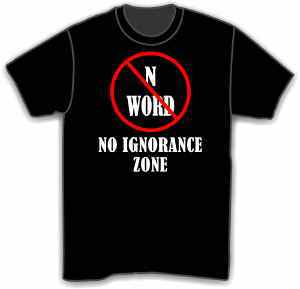

Decide how you will handle offensive language and racially-charged passages.

- Well before you introduce the novel as a reading selection to students, become familiar with the challenging parts of the text. Map out where they are in the text and have a plan for the “into, through, and beyond” of teaching that passage — how will you introduce it, how will you have students understand and move through the passage thoughtfully and how you help students understand the passage as part of the whole novel as they continue to get further in the book?

- Establish ground rules (and consequences) for discussion so you create a safe “container” for examining the text. Review your everyday class rules and norms and add a few extra for the discussion if necessary.

- Explain how you want students to handle reading offensive passage or words aloud. Decide before hand if you want to take the hierarchical approach and decide for them or a more collaborative approach – give three alternatives you (and parents) are comfortable with and have students decide after some discussion. It is usually a good policy to not have students read racially sensitive novels aloud in the class.

- Have a plan for managing potential violations of the discussion norms or disrespectful behavior. Actively manage disrespectful behavior such as laughing or using the offensive word after the discussion has ended.

Put the novel in historical context.

It is important when teaching racially-sensitive literature to put it into historical context. It is easy for us to judge older literary texts by current day standards.

- Learn about the social and political dynamics of the historical context for yourself Remember you are their “sherpa” who will be helping them navigate the reading. You must know the historical context at a deeper level. You must also know it from different perspectives, not just the “sanitized” or mainstream version.

- Have students construct a visual timeline. Help them answer these questions:

- Where does the novel fit within the history of the country?

- What other major social and/or political movements were underway at the time?

- What was the status of race relations in the country?

- Have students read primary documents so they can reconstruct the realities of daily life in the novel’s setting. For example, if the novel is set during slavery like Huck Finn, what were the structures and “rules” that kept the institute of slavery functioning? Do the same for the Jim Crow era.

- Have students read news reports on real life people that characters are based on. For example, introduce students to Margaret Garner, the real woman the character Sethe is based on in Find accounts of runaway slaves being assisted by Whites as in Huck Finn.

- Offer students the etymology and historical usages of racial epithets. Rather than simply debate where it’s ok or not to say the n-word or other racial epithet, help students know the word’s origins and its evolution. Do not assign this for students to do on their own. For example, watch together the short video, The N-Word through History to help students better understand why it is still a racially charged word in public spaces and in mixed company.

Show students how to read the text with a critical literacy lens.

Often the texts are more complex then that and students need to have tools for critical analysis so that they are able to recognize not only explicit racism but also implicit bias and what the author is trying to say (or fails to say) about them.

- Help students ask these critical analysis questions:

- In whose interest is this text written?

- For what purpose?

- Who benefits from telling the story from this point of view? Who is silenced? Who is harmed?

- Use a variety of discussion tools and structures so that students are able to interrogate the text. Offer multiples structures for discussion such as trios,microlab protocols, pinwheel.

Select companion texts or alternate novels.

It is important to provide students with companion texts to read before or along with a racially sensitive novel. Companion texts can offer another perspective that can illuminate the themes in the novel or provide a more holistic picture of the social, political or economic conditions in the novel.

Enabling texts on the other hand play a more supportive role by offering students of color a more empowering view of characters of color as resilient, resistant, resourceful and humane. According to Dr. Alfred Tatum, an enabling text offers validation of experience and instructive insight rather than be disempowering like a racially-charged novel that uses the n-word.

- Select companion texts that highlight the experiences of a different racial or gender group. What was happening for Latinos and Asians during this time?

- Use documentary video as a companion text. Africans in the Americas, Eyes on the Prize, Latino Americans (PBS), and other series may be helpful in complementing the text.

So, your turn. What has been your experience teaching racially sensitive literature? Leave a comment or come over to Instagram and share your thoughts.