This is the second in a series of a six part series on setting up the school year to be more culturally responsive.

In my last post, I shared that trust is the secret weapon of the culturally responsive teacher and it is the first thing that needs to be cultivated in the opening weeks of school. Trust is the source from which the culturally responsive teacher draws her authority, compassion, and cooperation.

Conventional wisdom then tells us that the next step is establishing rules, norms, and routines so that there’s order in the classroom.

But when teaching for cultural responsiveness, I believe the activation of a strong counter narrative is the second thing that should happen in the first six weeks of school.

We all know a narrative is just another name for a story. There are two types of stories in operation is society. First there is the dominant culture’s master narrative. This is the explanatory story society tells as to why things are the way they are. It’s the national myths like “America is the land of opportunity” that we a all grow up hearing and believe even when we know its true in reality. It spins a story about why some people experience social and economic advantages and why others are disadvantaged. It sells us on the idea of being a meritocracy while playing down the impact of racialization and implicit bias. There are explicit negative stories about certain groups of people such as “Those people don’t care about education.” (Fill in the blank about who “those people” are).

Then there’s what we call a counter narrative. It’s simply a narrative that counters or reframes the master narrative by highlighting other parts of the story, by telling the story from another perspective, or rejecting misconceptions or half-truths in the master narrative. The counter narrative is a form of identity development and affirmation that has a long history among different communities of color, growing out of colonialism.

Think of it like the movie, The Matrix. For rebels Morpheus and Neo, they are helping others see the real world (the counter-narrative) over the master narrative that programs the Matrix.

[Here is a quick aside. If you don’t believe there is a master narrative in operation that maintains the racialization of our society that gives some unearned advantages while giving others unearned disadvantage than you cannot successfully practice cultural responsiveness.]

Counter Narratives Support Student Identity and Agency

Why is this important during the first six weeks of school? Because the story we as teachers tell ourselves about who our students are and what they are capable of will guide our instructional decision-making for the rest of the year. For students, their personal narratives or explanatory story is the foundation of each one’s academic mindset.

The culturally responsive teacher recognizes that in the tradition of many culturally diverse students learning happens through story. Identity building and culture are passed along using story, retelling it as fables, myths, and proverbs. Education is full of negative master narratives about culturally and linguistically diverse students that we adults don’t always realize we pass along.

Here is the rub. Students hear us talking in these ways. Other teachers hear us talking in these ways. The teacher’s lounge is a breeding ground for negative memes and the perpetuation of the master narrative. These beliefs show up as off-handed comments we make to culturally diverse students that hurt their spirits.

For students, we give them only two choices when we promote a master narrative centered around a “less than” story: Either resist it (and you in the process) or accept it and let it become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Either way doesn’t lead to higher academic achievement. It leads to disproportionate discipline practices because we label their resistance to this master narrative as “defiance.” On the other hand, those students that accept the story develop a fixed mindset because they believe they can’t learn at high levels or can take on rigorous content.

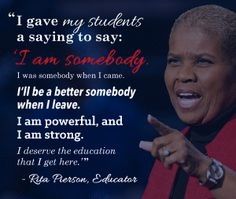

Let’s not get it twisted. A counter narrative isn’t just about hyping kids up on platitudes and positive thinking. And they are not just cheerleading chants. Telling them to work hard or be nice is not a counter narrative. Those are directions about how to behave, not affirmations of who you are as a person of color.

So, here are three things we can do to help students cultivate a positive counter-narrative.

1. Take the lead on challenging the master narrative from the front of the room.

In the media, we hear messages about “those kids” and their abilities all the time. The culturally responsive educator takes the lead on deconstructing master narratives around certain students. There are a number of these memes floating around:

- All Asian students are brainiacs and don’t need help.

- Poor kids can’t do higher order thinking.

- Kids from the inner city can’t code.

- Girls aren’t interested in technology.

When we hear these statements repeated as if they are true, we have to stop and challenge their validity and accuracy. Challenge by checking the assumptions behind the statement or asking for evidence to support that. In a matter-of-fact way, you will want to offer students strong evidence and several examples that discredit or invalidate a particular statement.

Recent Twitter changes offer an example of folks challenging the master narratives. The Twitter hashtag #IfTheyGunnedMeDown. The hashtag exposes the narrative the media continues to spin regarding the criminality of young Black men. They are sharing pictures that show them in causal settings with hoodies or throwing up a sign that are often taken out of context in the mainstream media and juxtapose them with pictures showing them as scholars at graduation or in suit and tie while out handling their business.

In a similar way the hashtag #NotYourAsianSidekick brought together thousands to challenge Asian-American racial and gender stereotypes.

2. Practice noticing and naming to help students craft a new narrative.

There are two parts to noticing and naming. The first is noticing and naming when students who repeat negative statements about their own capabilities or about the capabilities of others in their particular racial, gender, or language group. Without shaming or blaming, interrupt that behavior or point out how those statements aren’t true.

The other part of naming and noticing is drawing students’ attention to their learner identities, how they have grown as learners, and their natural gifts in the classroom, such as word play or the ability to make connections between different experiences or to make inferences. We call this perceptual bias. These are subtle skills that most students don’t have a name for and often think are that not important.

This part of noticing and naming is a critical practice for culturally responsive teachers. It activates the brain’s reticular activating system or RAS. The RAS is the brain’s 24-hour search engine that looks for events and experiences that confirm what is being named and noticed. When it finds them, it literally rewires its neural pathways to make permanent brain circuits that “hold” our story and use it to guide our actions and behaviors in everyday life.

The goal is to have students formulate and own their counter-narrative. That means you have to give them regular opportunities to speak their counter-narrative aloud to themselves and to others. For example, have student use the Success Analysis Protocol to look at and say out loud what progress or success they’re proud of at the end of a lesson or unit.

Use questions and prompts like these to notice and name:

- Remember during the first month when we had to really work at [fill in the blank]. Now you can do that automatically.

- Tell me what went well for you during the lesson.

- What interesting thing are you doing as a writer [ reader, thinker, or mathematician] today?

- You know what I heard you doing just now?

3. Using literature to help deepen the counter narrative

In addition to what students say to themselves as part of noticing and naming, Alfred Tatum says texts can play a key role in the process. He says the books students read (and the movies they watch) either promote the master narrative and are “disabling” to students of color or they can promote a counter narrative that is “enabling” in four important ways:

- The texts promote a healthy psyche for students

- They reflect an awareness of the real world (the socio-political context) that validates their experience.

- They focused on the collective struggle and resilience of culturally and linguistically diverse communities.

- They served as a road map for being, doing, thinking, and acting as characters navigate racial, language, and gender politics in the larger society.

You can use these four characteristics as a checklist for selecting books for classroom libraries. Also consider using an enabling texts as companion text paired with mainstream books mandated in the curriculum. You can use them as mentor texts for writing as well.

So, how are you helping culturally and linguistically diverse students reframe their narratives? What tools and techniques do you use at the start of the school year?