In my last post, I talked about call and response as the first tool in our instructional CR toolkit.

Whether you use call and response for academic review or to promote thinking, it is important to understand the neuroscience behind the tool so that it doesn’t seem so mysterious or magical.

Instead, it can help you understand how to use it with more creativity and flexibility. It sounds nerdy, but the science behind cultural responsiveness is really important because it gives us insight into how culture wires our brain for learning.

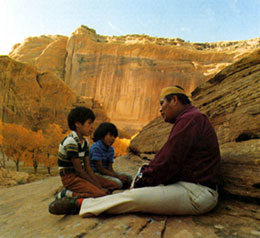

Why does a technique like call and response work for children of color? It has to do with the fact that their cultural roots are deeply connected to the primary ways learning happened in an oral culture. Our forefathers and foremothers knew how the brain worked without calling it “brain-based learning.” They understood the need to make sure children remembered what was told to them.

Over thousands of years, most indigenous oral cultures perfected these methods to ensure cultural information was transmitted from generation to generation. Today, these methods are deeply ingrained in the way learning happens at home for many children of color, even if most adults aren’t always conscious of it. If asked about it, they’d probably say “That’s just the way we did it when I was a kid.” Add to tradition, the socio-political contexts that made it illegal or difficult for some to learn to read during and after slavery. Or the limited access early immigrants had to formal education. Many margnalized racial groups had to continue to rely on their oral traditions for everyday learning.

So, let’s break down the neuroscience of call and response to better understand how it works. It draws on three aspects of brain’s learning process: attention activation, firing and wiring, and mirror neurons.

Attention Activation

Attention is the first step in learning. We cannot learn, remember, or understand what we don’t first give our attention to. The “call” from the teacher that begins the process alerts the student’s brain that something is about to happen. The brain becomes curious and begins to pay attention in a different way. The “call” part of call and response triggers the student’s Reticular Activating System or RAS for short.

The RAS is that part of our brain that controls our ability to become mentally alert and focused, among other things. What gets the RAS really going is novelty (something new,surprising or puzzling), physical sensation, and high personal relevance — in that order.

Activating the RAS is critical in a culture structured around an oral tradition where you transmit information from one person to another.

It’s located in our older, emotional brain and doesn’t respond well to words or verbal commands. That’s why you can’t simply tell a student to pay attention. You have to entice the brain with something that makes it curious or emotional (in a positive way).

This is why call and response is done in an lively, energetic way. It activates our RAS and helps us generate mental energy and focus.

The take away here is to ritualize how you activate students’ RAS to turn on their attention. Start a round of call and response with a physical signal — a flip of the light switch, a specific number of hand claps, a chime, or a train whistle to activate their RAS and let them know it’s time to pay attention.

Firing and Wiring Together

Remembering is the next critical part of the learning process. Call and response is designed to help the brain remember. Remembering seems like something we do that’s effortless, right? But, in reality, remembering is more complicated and fragile than we imagine. Call and response helps strengthen a student’s ability to retrieve important information that has been learned earlier.

Every time a student engages in call and response, the information reviewed is driven deeper into his long term memory. This makes it easier for him to retrieve this information whenever he wants. When processing information, brain cells called neurons communicate with each other through a cascade of electro-chemical reactions. This is referred to as “firing” because of the electrical current involved. If you give enough focus and concentration on something, the brain will start to fire neurons in new patterns. This new pattern is called a neural pathway and is the beginning of a new memory.

When call and response is connected with rhythm or chanting, it helps neurons fire and “wire together,” meaning the rhythm gets permanently associated and connected to the information being remembered, making it easier to retrieve. It’s the same reason we remember the ABC song or those catchy School House Rock episodes. The music or catchy jingle is wired together permanently with the information the creators wanted us to learn.

Mirror Neurons

We are social creatures who are hardwired for connecting. That’s why there’s wisdom in call and response as a communal learning activity. But there’s science behind it as well. The human brain contains a special class of cells, called mirror neurons, that fire when a person sees or hears a relevant or emotionally charged action being carried out by others.

Mirror neurons seem to be an extension of socio-cultural learning theory that says people learn most effectively in a social context.

Sociocultural theory grew from the work of seminal psychologist Lev Vygotsky. According to Vygotsky, “Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first, between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological). This applies equally to voluntary attention, to logical memory, and to the formation of concepts. All the higher functions originate as actual relationships between individuals.”

Kendra Cherry author of the Everything Psychology Book

You might be tempted to think that call and response provides kids who don’t know the material a chance to hide in the crowd. But when we remember the presence of mirror neurons, it’s easy to reframe call and response as an opportunity for those students to learn from their peers in the moment. The brain is firing and wiring as they hear the right responses from others.

When planning your units and daily lessons, ask yourself how are you making the most of the RAS system or mirror neurons. Remember that getting students actively involved in the learning traditions of their culture help develop strong neural pathways that become the framework for deep background knowledge and understanding.